Over the last ten years, a recurring theme of our clean cooking work has been the need to define clean cookstove adoption based on measured stove usage rather than sales or ownership. There is far too much evidence of improved stoves falling into disuse for us to assume that distributing a clean stove will have the intended impact on air quality, wood fuel use, or health. As a result, our sensor-based monitoring systems have evolved around this question: how can we discover the ground truth of what’s actually happening in people’s kitchens?

This need continues to grow as the clean cooking sector looks to modern fuel and energy sources for cooking, including LPG, ethanol, biogas, and electricity. With near-zero emissions of particulates and indoor air pollutants, these next-generation solutions have the potential to transform women’s lives around the world. However, given the increased fuel cost and a completely new cooking habit to embrace, how much will they be used? How do all of us in the clean cooking sector ensure that the right infrastructure, price, and training are in place so that women can use modern energy for the majority of their cooking, rather than as a supplement to their traditional cooking?

One of our first forays into measuring the use of modern energy cooking was with our pilot project in Nigeria, where we sought to identify the right stove to distribute to rural women using a climate finance model. Our goal was to identify the stove that showed the highest level of sustained adoption—that is, consistent usage over time—so that we could be assured women would receive a stove that met their needs. Alongside the improved biomass, LPG, and ethanol stoves that we were testing, we also monitored traditional stove use which gave us the opportunity to ask more questions that revealed what’s really going on. Questions like: how much do households cook on their full stack of stoves? And, by calculation, what were total household emissions?

Sensor Data: What We Measure and What We Can Learn

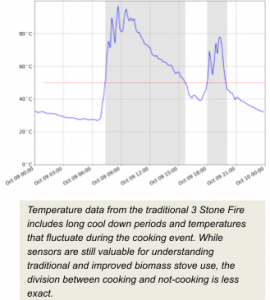

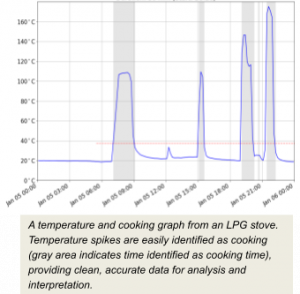

Temperature sensors use heat as an indicator of cookstove use. The data generated by temperature sensors produces three types of measurements:

1. Minutes spent cooking

2. Number of cooking events

3. Time of day when cooking occurs.

When we have emissions data from lab or field tests, we can also use those measurements to approximate actual emissions. In other words:

Time spent cooking (sensor data) x Emissions rate (lab tests) = Actual emissions measurement

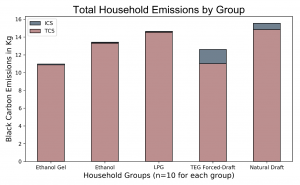

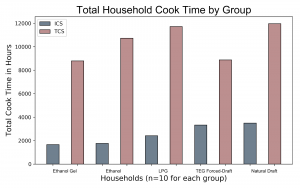

Our Nigeria pilot included 5 clean/improved stove types monitored alongside the traditional Three Stone Fire: LPG, ethanol, an ethanol gel stove, a forced-draft TEG stove (improved wood-burning stove with a battery-powered fan for efficiency), and a natural draft improved wood stove (improved wood stove that is more efficient by design with no battery or moving parts). The three liquid-fuel, modern energy stoves were the cleanest options, with negligible emissions of black carbon, the leading offender of indoor air pollution. The total reduction of household emissions, however, is only as significant as the extent to which clean cookstove use actually offsets traditional cookstove use. When we look at our calculated black carbon emissions to understand a household’s combined “stack” of traditional and clean stove use, we see that households with the cleanest stoves do not have the lowest overall emissions. Households with the LPG and ethanol stoves had the highest usage of traditional cookstoves (TCS), and therefore the highest total household emissions after the natural draft stove.

These findings are just a snapshot and should not be used to draw any conclusions about any of these stove types. This data does not tell us which stove type best offsets TCS use, nor which stove type will result in the greatest black carbon reduction. Rather, this data reinforces our recurring theme: actual usage matters and potential impact is not the same as actual impact.

What’s Next?

Monitoring traditional cooking is not always the most effective nor feasible way to discover the ground truth. In Nigeria, our traditional cookstove data was collected by a team of trained entrepreneurs who were paid to ensure that temperature sensors were properly installed and maintained on each and every traditional and improved stove. Even with excellent on-the-ground support, the variability of traditional cooking where stoves are regularly taken apart, rebuilt, and moved, makes sensor-based monitoring difficult and potentially inaccurate.

Directly measuring the ground reality of cooking is difficult at scale. If we can’t directly measure traditional cooking, then what can we infer from direct measurements of improved cooking? Is there an amount or frequency of clean cookstove use that we can confidently assume is offsetting traditional use? Is there a threshold of clean cookstove use that we can look for to say yes, we are making a difference? These are the kinds of questions we should be asking ourselves as a sector if we want to make a long-term impact on the lives of millions of women.